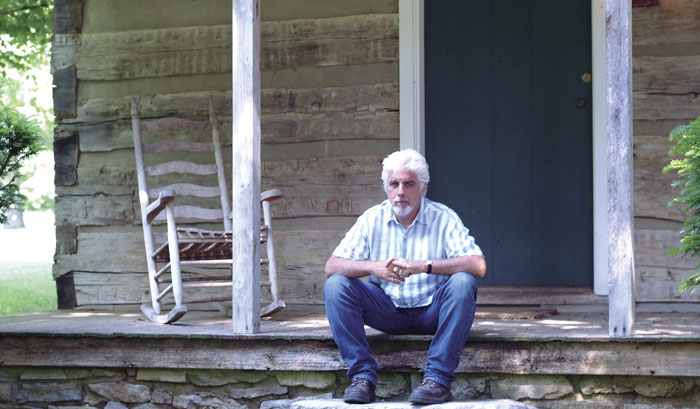

Michael McDonald is responsible for some of the most beloved songs of the last three decades. After leading the Doobie Brothers through the most successful phase of their career with hits like "Takin' it to the Streets," "What a Fool Believes," and "Minute by Minute," McDonald embarked on a distinguished solo career whose highlights include rousing duets with such R&B greats as James Ingram and Patti Labelle. His husky baritone voice and dramatic piano-based tunes remain one of the most iconic sounds in pop.

Last year, McDonald revisited his '60s R&B roots with Platinum-selling Motown, a tribute to the songs of the great '60s/'70s label. Now he's following up on that success with the second installment, Motown 2, to be released later this year. We recently checked in with McDonald at his Nashville studio. Thoughtful and modest, he discussed the great R&B music that helped define his style and his own songwriting strategies.

Some of your Motown tracks are faithful remakes, while others take the songs in surprising directions. How did you decide which approach to take?

We look in every direction before we settle on a style. Sometimes we felt that a song deserved to be done in the original style. for example, our versions of Thom Bell's "Stop, Look, Listen (To Your Heart)" and The Four Tops' "Reach Out (I'll Be There)" are faithful to the originals. But we took Stevie Wonder's "I Was Made to Love Her" in a radically different direction and made it a modern urban rock track. Or take The Supremes' "Reflections," which originally had a psychedelic, '60s sound. We did it with a lilting, organic, African folk-style groove. Sometimes it's hard not emulating the originals, because I grew up knowing and loving those records.

I'm not always actively writing, but I'm always writing. My songwriting notebooks are always filled with more napkins and envelopes than actual pages.

Have you played these songs all your life?

Very much so. I was playing a lot of them in clubs when they were radio hits for the first time! I started out as a Top 40 musician with R&B dance bands. Those were the better-paying club gigs, because people were there to dance - not just stand around or twirl like they did in the acid rock clubs. I was playing those gigs from the time I was 14, so that kind of music was a staple of my style. Two of my biggest songwriting influences were the great Motown writing teams, Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson and Holland, Dozier & Holland. Their songs always figured heavily in my psyche when I was writing.

You can hear that influence in the way you build up excitement in a song with surprising modulations and key changes.

That's a gospel influence, I think. Changing keys to raise the passion quotient was something that I noticed about gospel tunes when I was growing up. Of course, Ashford and Simpson are a great example of people from a gospel background bringing those sensibilities into the R&B world. They wrote so many great songs: "Ain't No Mountain High Enough," "You're All I Need to Get By." "Ain't Nothing Like the Real Thing." All those rich voicings, passionate chord progressions, and soulful lyrics! Almost anything they wrote can become my favorite song while I'm listening to it.

You've made great duet records. Why does that format appeal to you so much?

I haven't done all that many duets - I've just had success with the ones I've done. for example, the first Motown record had no duets, though the second one will. But I do love duets. There's nothing better than that spark that can happen in a duet, the sense that it's much more than the sum of the parts. Actually, I've always enjoyed working with other people. A big part of me still misses just being a regular member of a band. when I play on the road, I try to remain cognizant of the fact that I am part of a band. In order for me to do my best job for the audience, even as a solo artist, I have to be aware of that.

How does being a keyboard player affect the way you sing and write?

Well, when you're playing and singing at the same time, it's sort of a package deal. There are things you do differently with your voice, because it's in symbiosis with what you're playing. But on the other hand, I think all good singers instinctively align themselves with whatever instrument carries the main melody and chord progression. At least, singers I enjoy most always give me a sense that they know what's going on with the underlying chord progression, beyond just the basic notes of the melody.

Do you write at the keyboard?

Mostly, though I also write on the guitar. I don't play it very well, but enough to write. I've always written some guitar songs. In fact, Alison Krauss has recorded "It Don't Matter Now," a song I wrote on guitar when I was 19. I don't know where she found it - I hadn't thought about it in years.

Are you always composing, or only when you're inspired?

I'm not always actively writing, but I'm always writing, if that makes any sense. I'm always looking for a pen or paper to get down some idea that popped into my head. Later, I look back at the ideas. Sometimes I hate them, but sometimes I'm very glad I wrote them down. My songwriting notebooks are always filled with more napkins and envelopes than actual pages.

Are you the type of writer who tinkers and edits a lot? Or do the good songs come quickly?

A little of both. There were times when I sat down at the piano, not even sure if I would write anything, and then created a complete song in 15 minutes. "I Can Let Go Now" [from If That's What It Takes] came to me like that. So did "Matters of the Heart" [from Blink of an Eye]. I'd just put my kids to sleep, then I sat at the piano and turned on the cassette machine - luckily! - and wound up playing the song in full, with almost all the lyrics, on the very first pass. But sometimes it takes a long time to work something out. And sometimes you discover you're actually writing two different songs - maybe part of one is supposed to be the bridge of another.

You've written solo and with other writers.

Those are two different worlds to me. When I write alone, the results are usually a little stranger and abstract and introspective than when I write with someone else. I've always done a lot of collaborative writing, and I've done even more since I moved out here to nashville a few years ago. But at the same time, I've learned to write alone again.

You've been working with a Yamaha Motif ES8 lately.

Yes. I love the Motif, and I think it's the best all-around keyboard out there. A lot of companies have some version of that sort of all-in-one programmable keyboard with sampling. But what keeps me using Yamaha's version is the fact that the programmers really seem to understand the overall ambiences of the sound, those little characteristics that really make a difference when you're recording. For example, you can hear the sound of the finger coming off the string on the upright bass sounds. The people who did the R&D on that keyboard really get how little things like that really make a difference when you're recording. The Motif has a great collection of sounds. The electric piano library is vast and wonderful. The string sounds are great, with all the variations in timbre you need. All the sounds have realistic attacks, decays, and releases. The keyboard feels great - when I perform on the Motif8, it can really feel like I'm playing an acoustic piano. And I like the way it's so easy to select and organize your sounds. They're all sorted by categories, and you can create your own. It's just so versatile. for the price and the application, the Motif has to be the best keyboard of its kind. I use mine for live shows, and rely on it endlessly in the studio as well.

Do you use the Motif sequencer?

Actually, I don't do a lot of sequencing in general these days.

Why not?

Well, we used to do a lot of sequencing in the studio so we could have the freedom to change sounds or keys while we're working. when sequencing first started to come into its own, that was very appealing. But now I find I'm getting back into the feel of recording things live, and I like not being boxed in by a sequencer. I sometimes use drum loops for writing, just to have something to work out a song without losing the moment. But since I usually work with a live drummer these days, we're most likely to make our own loop, and that can mean something very different from strict clock time.

Do you have a favorite among your records?

Well, the Motown records are up there. I enjoyed doing Blue Obsession and Blink of an Eye, and was pleased with the results on both. Those were times when I finally found a certain resonance that I'd been looking for, for a long time. Sure, there are some things I hear now and think, "I could have done better." But on the other hand, some songs seem to have more meaning now than then. Like "Blink of an Eye" - that song tends to mean more to me as I get older. The song was about watching my young kids and seeing their wonderment in life all around them. how they accept everything with a certain kind of loving understanding that we lose as we get older. The song was saying, "Don't let a minute go by unappreciated. It all goes past in the blink of an eye." Those words just have a lot more meaning after fifteen years of life experience.

And what comes after Motown 2?

We're already working on another studio record of original compositions. I think it will be a little more "below the radar" - very personal music, perhaps with a little less production value. Maybe some things where I'm playing all the instruments - God forbid! [Laughs.] But I like things like that, because they have their own unique vibe.