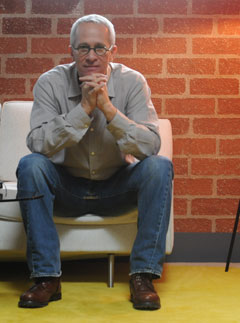

Check the credits of your favorite box-office smash from the past two decades, and there's a good chance you'll see James Newton Howard listed as composer. Howard has contributed music to more than 100 films, from romantic comedies to action thrillers to sci-fi blockbusters, earning Oscar, Grammy, and Golden Globe nominations or awards along the way. He's also contributed to the small screen with compositions like the Emmy-nominated main theme for the long-running series ER.

Despite his big-picture success, film music wasn't Howard's first career choice. Before writing music for movies like Pretty Woman, The Fugitive, The Sixth Sense, and I Am Legend, Howard toured and recorded as Elton John's keyboardist and orchestrator, then chalked up pop hits as a producer and songwriter with such artists as Cher, Chaka Khan, Barbra Streisand, and Earth, Wind & Fire.

Just about every aspect of music-making is necessary in film music: working with a rhythm section, arranging an orchestra, programming synthesizers, composing.

"It was never my intention to work in film," he says. "I started off as a classical musician--I was a piano performance major at USC. After that I played in lots of rock and roll bands, finally in Elton's band, and then I did lots of sessions and arranging."

Howard's first foray into film composition came in 1985, when he was asked to score the comedy Head Office, starring Judge Reinhold and Danny DeVito. "I was nervous, and very reluctant to do it," he remembers, "but in the end I just decided, why not? And it was love at first sight. I realized I had really found my niche--I was able to bring together everything I had learned in the pop music world. Just about every aspect of music-making is necessary in film music: working with a rhythm section, arranging an orchestra, programming synthesizers, composing. So it was a perfect fit for me, and I haven't stopped since."

Howard is currently scoring several films, including the George Clooney comedy Up in the Air by writer-director Jason Reitman, and an upcoming M. Night Shyamalan adaptation of the animated Nickelodeon series Avatar: The Last Air Bender. He's also returning to his pop music roots with an unlikely-sounding project: a Josh Groban disc produced by Rick Rubin. "We're trying to do a very different kind of album," he explains. "It could be just orchestra and Josh, with no rhythm section. I'll be contributing on several fronts, from arranging and orchestrating to some level of co-producing."

In both his pop and film music, Yamaha keyboards have been a recurring theme in Howard's musical life. As a young session player and producer, he helped demonstrate the capabilities of Yamaha synths such as the GS1 and DX7. "I've been involved with Yamaha since 1982," he says. "I used to perform at NAMM shows, and tour, and do all kinds of things on behalf of Yamaha keyboards, which I've always loved."

Even now, Howard remains a fan of Yamaha's 1980s-vintage KX88 weighted keyboard. "I still use a Yamaha KX-88," he says. "I've always used the KX-88! I buy up every one I can find. I've got a stack of them, because I love the feel of that keyboard."

Another longtime companion is his 6'11" Yamaha C6 Conservatory Collection Grand. "It's a beautiful piano," says Howard. "It's got a very playable action, very solid and even. It sounds rich, dynamic, and bright without being harsh. It's just a great-sounding instrument."

With three to five major film projects each year, Howard relies on Cubase 5 on the PC to simplify his sequencing tasks. "The ease with which I can manipulate audio has become better and better," he notes. "The technology has made it possible for me to work about 35 times faster than in the old days! Though I learned long ago that I would be more effective as a composer if I chose what I spent my time doing. So I don't program as much as I used to, although I'm very facile with all the soft synths."

But despite the technological changes, Howard's fundamental approach to scoring remains the same. "The most important thing," he says, "is to write music without getting hung up in the beginning on the way it interacts with the picture. That's what I always tell young composers: When you start a project, turn off the movie and just write something that feels like it's related to the picture, something that feels good. Then put that up against the picture and see what percentage of it works. For me, the best thing about working on a movie is the instant gratification of putting music up against picture and immediately seeing the change. Seeing things in the film that the director never knew were there."

Any other advice on working with directors? "Be a great listener," Howard says. "It's a collaborative industry--if you don't want to collaborate, you shouldn't do it. And be prepared to be thick-skinned about your music, because it's going to be swamped with sound effects and that pesky dialog. Be prepared to be a psychologist, and a friend, and defend your work enthusiastically, but always remember that it's their movie."

(Photography Credit: Rob Shanahan)