The Structure of the Pipe organ

Sliders and the wind-chest

Sliders determine the timbre

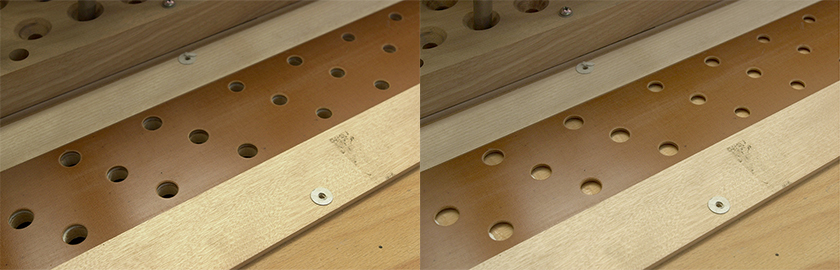

Sliders are slats with many open holes, and moving them between positions determines whether or not wind is able to pass. When the organist pulls the stop, the holes on the respective slat align so that wind can pass, and sound is produced. Conversely, when the stop is pressed, the holes will no longer be aligned and the wind will no longer be able to pass.

Wind can pass (left), wind cannot pass (right)

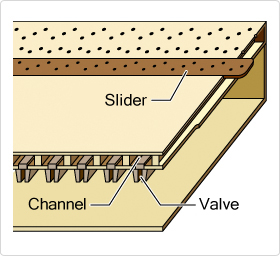

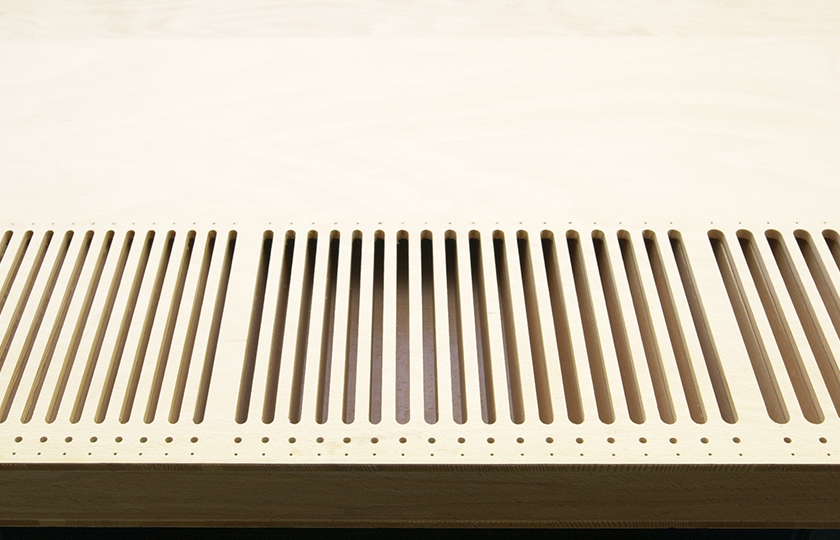

A pipe organ with three timbres has three sliders. In the wind-chest there are open holes for each of the three timbres, with three sliders in place for each of the timbres above the wind-chest and the pipe-board, on which the pipes rest, placed above that.

On the top of the wind-chest, the holes and slider for the three timbres.

The wind-chest as the heart of the pipe organ

If the wind-chest is turned upside down, a series of vertical grooves can be found. The grooves appear to be cut about half-way into the wind-chest, but actually, beneath the board, they extend into narrow, partitioned chambers. As these are the passages through which the wind passes they are referred to as "channels," and they correspond to each key of the manual. The channels are shaped like miniature ladders.

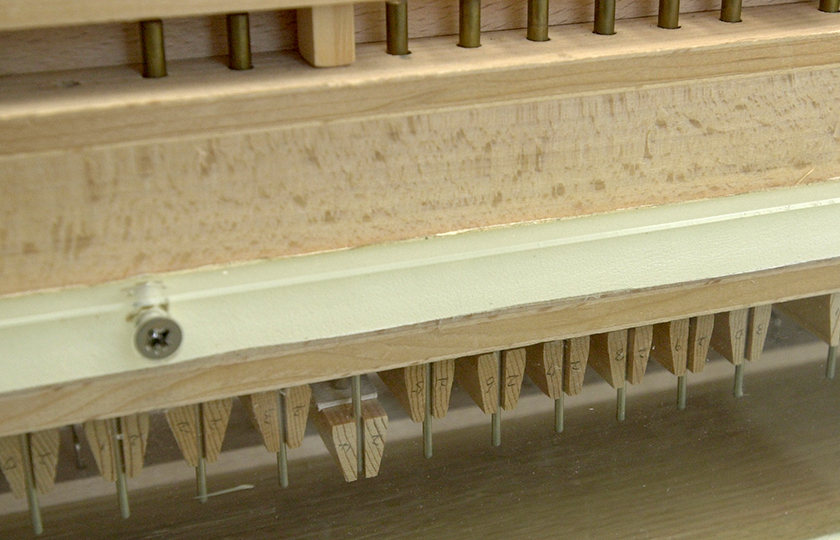

When a manual key is pressed, the valve that covers the groove opens and wind enters the channel, passing through the sliders where the holes are aligned and continuing into the pipes above. This is how sound is produced. It is for this reason that the wind-chest can be described as the heart of the pipe organ.

Wind-chest structure

Cross-section of the wind-chest, grooves extending into the channels

Valves inside the wind-chest, with a single valve, corresponding to a key pressed on the manual,lowered

Musical Instrument Guide : Pipe Organ Contents

Origins

How to Play

How the Instrument is Made

Care and Maintenance

Trivia

- Various sizes, from large-scale to pocket-sized

- Can you tell an expensive instrument from its sound?

- Changing fashions in the number of manuals

- Partial bass range

- Delay between play and sound

- Appreciating the aesthetics of churches

- Pipe organ treasures in Tokyo

- Sound that varies according to where it is heard