How to Play the Saxophone

The saxophone is a transposing instrument

Notes and scales

In the English-speaking world, notes are known by letters, with Do equal to C, and going up alphabetically to G from there, then starting over.

For example, when a tenor saxophone, a B♭ instrument, plays an F scale, it goes like this.

1. Naturals

Notes that are neither sharp nor flat are called "natural." This table shows the names of notes in Germany, enpan, Italy, France, the UK, and the US.

| Germany | C | D | E | F | G | A | H | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Ha | Ni | Ho | He | To | I | Ro | Ha |

| Italy | Do | Re | Mi | Fa | Sol | La | Si | Do |

| France | Do(Ut) | Re | Mi | Fa | Sol | La | Si | Do(Ut) |

| UK US |

C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

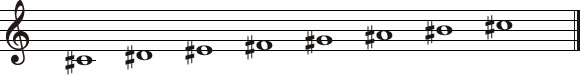

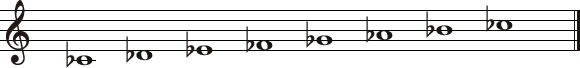

2. Accidentals

Notes with signs indicating flats (♭), sharps (♯), or other changes, are called accidentals.

1) A sharp (♯) refers to a tone one half-step above a natural.

| Germany | Cis | Dis | Eis | Fis | Gis | Ais | His | Cis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Ei ha | Ei ni | Ei ho | Ei he | Ei to | Ei i | Ei ro | Ei ha |

| Italy | Do dieisis |

Re dieisis |

Mi dieisis |

Fa dieisis |

Sol dieisis |

La dieisis |

Si dieisis |

Do dieisis |

| France | Do(Ut) diesis |

Re diesis |

Mi diesis |

Fa diesis |

Sol diesis |

La diesis |

Si diesis |

Do diesis |

| UK US |

C sharp | D sharp | E sharp | F sharp | G sharp | A sharp | B sharp | C sharp |

2) A flat (♭) refers to a tone one half-step above a natural.

| Germany | Ces | Des | Es | Fes | Ges | As | B | Ces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Hen ha | Hen ni | Hen ho | Hen he | Hen to | Hen i | Hen ro | Hen ha |

| Italy | Do bemolle |

Re bemolle |

Mi bemolle |

Fa bemolle |

Sol bemolle |

La bemolle |

Si bemolle |

Do bemolle |

| France | Do(Ut) bemole |

Re bemole |

Mi bemole |

Fa bemole |

Sol bemole |

La bemole |

Si bemole |

Do bemole |

| UK US |

C flat | D flat | E flat | F flat | G flat | A flat | B flat | C flat |

This covers the basic notes, but there are also double sharps (two half-steps up, indicated by ♯♯), and double flats (two half-steps down, indicated by ♭♭).

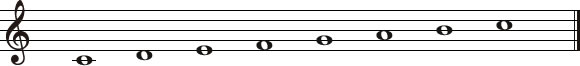

Playing an actual ("concert") F scale

An F scale is a scale that begins at F. On a piano, an F major scale has one flat: F, G, A, B♭, C, D, E. When this same scale is played on a tenor saxophone, however, what is actually played is this: G, A, B, C, D, E, F♯

Playing a tenor saxophone F scale

This can be played with the normal saxophone fingerings: F, G, A, B♭, C, D, E

Transference between instruments

Saxophones essentially all have the same fingering, so those fingerings carry over between them.

When changing from an alto sax to a soprano sax, for instance, the alto has an E♭ tube, while the soprano has a B♭ tube, meaning that even when you play the same score, different sounds are produced. Unless the score itself has been changed beforehand, the player must transpose the notes as they play. The mouthpieces are also different between instruments, so it may take some time getting used to each one.

The difference between the score and the actual sound

Because the saxophone is a transposing instrument, when changing from one instrument to another, such as from an alto to a tenor, playing the same score will produce different actual sounds. Transposing instruments produce sounds different from those in the score and those produced by non-transposing instruments (the piano is the standard for actual or "concert" pitch).

Tenor saxophones are tuned to B♭, and alto saxophones are tuned to E♭, but when playing the same note on a score, the fingerings are the same. When a C is played on a tenor saxophone, however, the actual pitch produced corresponds to a B♭ on a piano, and in the case of an alto saxophone, playing a C actually produces an E♭.

What that means in practice is that to play a concert F major on a tenor saxophone, the player should play a G major on the score. For an F major on the alto saxophone, the player should play a D major on the score.

This arrangement was originally conceived with the intention of making saxophone fingerings easier. When actually playing in a group, however, because it is more convenient to use names for the notes that are common to everyone, the notes are referred to in terms of actual sounds (hence term concert pitch). There is no need to be overly concerned with the details of this process when first starting out. If you continue to practice, playing from a score with both the written and actual pitch on it, you are sure to get used to it soon.

Enharmonic equivalents

In a score, there are a variety of situations in which you may encounter C♭ or F♭. In modern musical notation, however, C♭ is actually the same pitch as B natural, and F♭ is actually the same pitch as E natural. These sounds are known as enharmonic equivalents.

Technically speaking, there is a very slight difference between C♭ and B natural, but based on the current even tuning of intervals on the piano, the sound actually produced for each is the same.

In terms of fingering, B natural and E natural are the same as their enharmonic equivalents, but because wind instruments allow for slight variations in intervals, players should be mindful of the fact that the interval may change slightly through the piece.

Lots of sharps in the score

Tenor and soprano saxophones are in the key of B♭, just like clarinets. All three of these instruments produce a B♭ when playing a C on the score. That is why in order to produce the same C pitch as keyed instruments or the flute (concert or "written" C), they must actually play a D. Because the D major key is a whole step above the C major key, it contains two sharps.

Since alto and baritone saxophones are in E♭, (meaning they produce an E♭ when playing a written C), in order to produce an actual C, they must play an A, which is a perfect third down from C. In this case the key becomes A major, meaning that there are three sharps.

Sheet music for wind instruments are nearly always only parts of the score, so it is arranged for the key of the instrument it is written for.