Music creation should be possible for everyone, no matter the physical challenge.

(Part 1)

Vahakn Matossian / Designer and Inventor

Design meets music and creates new instruments.

Vahakn Matossian develops musical instruments that people with disabilities can play. Raised in a family with a rich musical background, he has chosen product design for his career. We asked Vahakn what drew him into the development of original musical instruments at Human Instruments and his activities that combine music with product design.

A childhood of abundant music. First composition at 15 years old.

Musically speaking, I grew up in a exciting environment. My father, a composer of contemporary music, at one point collaborated with Karlheinz Stockhausen. My mother, a writer, published a biography of composer Iannis Xenakis. I enjoyed listening to my parents’ huge collection of vinyl records, experiencing every musical genre you can image, from classical to rock and reggae.

At age 11 I became a fan of The Prodigy, a band introduced to me by friends. Though still too young to see them live in dance clubs, I got my first taste of rave music through their tracks. From there I took an interest in other music scenes such as jungle, Drum ‘n’ Bass, and the hardcore reggae of Jamaican immigrants in London. Then my brother and I started dabbling in DJing to get a taste of the party scene.

I took lessons on the guitar, piano, and drums. A few years later, at the age of 15, I learned how to work a sequencer at a local music school where my father taught. The sequencer helped me understand how music was constructed. It attracted me to the idea of composing my own pieces.

Enchanted by both playing and composing, I got the idea of becoming a professional musician. But the practice I needed to get there daunted me. In time music became more of life-shaping theme for me than a profession to aspire to.

Discomfort with the commercial restrictions of the design world.

Adept at making things with my hands since childhood, I majored in design and sculpture at the University of Brighton. Those disciplines, I expected, would provide useful skills for making objects related to music in the future. Studies in music itself appealed less to my practical instincts: all I needed to make music were my home-studio, a turntable, and pair of headphones. After university I spent a year working in a company, then decided to take a Master’s degree at the Royal College of Art. The degree set me on track to several successful years as a designer with commissions at my studio in London and a budding presence at various design and art exhibitions around the world. Yet my work only seemed to be recognized and valued for what it could do in the marketplace. Ultimately, it became clear, my works were only enjoyed by the well-to-do. So I came to despise what I did.

An interest in ecology bolstered my objections against mixing the creative with the commercial. My first ambition as a designer was to develop environmental products such as a robot to clean the seabed or a grain-based plastic material. But then I was thrown into the competitive fray of the design world in London. With talented rivals everywhere one looked, being choosy about the commissions one took wasn’t an option.

With a stroke of great luck, my father just then became a launching member of the British ParaOrchestra, the world’s first orchestra for people with disabilities. Having always respected my father and what he does, I decided to help him with this initiative.

The orchestra’s performance stirred a respect in me that deepened my involvement.

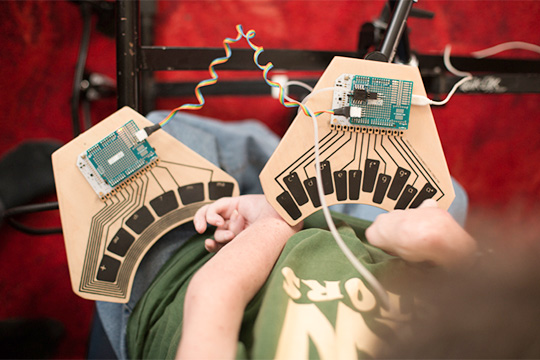

I first joined the orchestra as a project supporter rather than a designer. It quickly became clear that very few musical instruments were adapted for use by disabled people. One in five people in UK are registered as having disabilities, from young to old. How many thousands of them, I asked myself, could play musical instruments or wished they could? I began to develop musical instruments that people with disabilities could play.

Another turning point came as I listened to the performances of several disabled musicians in the orchestra. Astoundingly, these performers played with a sensitivity I had not-so-far experienced from their non-disabled counterparts. Not for an instant was I reminded that they were people with disabilities. After their performances they candidly told me about the difficulties they had to overcome. Their passion for music, undiminished by their disabilities, won my greatest respect. A desire to help people like them spurred my efforts to drive Human Instruments forward.

- Vahakn Matossian / Designer and Inventor

- London-based designer Vahakn Matossian grew up in a family of musical talents and has become a successful DJ musician himself. Vahakn’s involvement in an orchestra his father helped organize for people with disabilities inspired him to start “Human Instruments”- a company that develops musical devices that even persons with heavy physical challenges can play.

Interview Date: