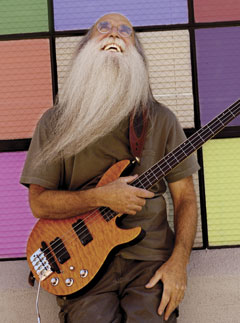

After playing bass on well over 2,000 albums, wouldn't session work get a little, well, old? "Absolutely not," insists Leland Sklar. "To this day, every time I get a call to do something, I think, 'Oh man, this is so bitchin'!'"

YOU'VE HEARD SKLAR'S WORK ON THE HITS OF PHIL COLLINS, NEIL DIAMOND, Hall & Oates, Dolly Parton, Diana Ross, Vince Gill, Clint Black, Trisha Yearwood, Lyle Lovett, Celine Dion, Wynonna Judd, Robbie Williams, Olivia Newton-John, Rod Stewart and many, many others. But the Milwaukee-born, LA-bred bassist is probably best known for helping craft the '70s West Coast singer/songwriter sound via his work with Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, Crosby, Stills & Nash and, most notably, James Taylor.

I still can't get over the fact that this is what I get to do for a living.

"I pretty much owe my career to James," says Sklar. "When he hit, everyone saw that this was a viable form of music, not just something for the coffeehouses. There were a lot of great writers and groups in LA at that time: Jackson Browne. The Eagles. The Flying Burrito Brothers. Poco. It all became this signature of a certain West Coast sound. And you know, a lot of what's happening in Nashville right now goes straight back to that early-'70s LA sound."

According to Sklar, the early '70s sessions that made his name marked a sea change in the nature of session work. "In the '60s, there were many great session players in LA--people like Hal Blaine and Carole Kaye, players I was in awe of then and now. When they came in to play a session, the music was usually carefully arranged in advance, and they proceeded to play the hell out of it. But by the time I started working, much more of the arranging work was laid on the players' shoulders. The artist would often come in with just a song and a guitar, and we had to invent the music around it."

The key to creating music that way, says Sklar, is entering the song's emotional world. "It's imperative. The fault I find with a lot of musicians is that they play for themselves, without getting inside the song. If there's an emotion that requires a whole note, you play a whole note. You don't think, 'This is boring and I should be playing more.'"

Not that Sklar is a total minimalist--his tracks are alive with subtle variations and tuneful connecting lines. How does he balance the melodic impulse with holding down the groove?

"You wait for your moments," he replies. "For places where you can add a little signature, a little touch of personality. I was fortunate in that I got to listen to players like Paul McCartney, Bob Mosley from Moby Grape, Jack Bruce from Cream. They all crafted bass parts that had both melodic content and deep pockets. That's where I've always felt it too. I tend to be a very intuitive, non-intellectual player. When the red light goes on, I just try to go with my gut. I try to make it as deep and visceral a response as I can."

Sklar has used Yamaha basses throughout his career. "In 1972," he recalls, "the Yamaha guys came over from Japan and gave a lot of players instruments for evaluation, and I still have mine. It's the bass I played on James Taylor's 'Your Smiling Face.' It's a funky old thing, but it's really great. More recently I've had great luck with a lot of the TRB basses, especially one particular TRB5 fretless. And I have a real passion for the BB Series basses. I was planning to retrofit one of my old BB basses with a new tremolo bridge, but John Gaudesi at Yamaha Guitar Development wound up making me a whole new instrument designed around the bridge. It sounds great and plays evenly. I've used it on many projects, and it never disappoints me. I've been really happy with everything I've ever had from the Yamaha guys."

Sklar admits he regrets some of the ways his profession has changed over the decades. "I don't like to be one of those guys who can only talk about the good old days, but I miss the great bands we used to have. We were always in the same room at the same time working together. Nowadays, two-thirds of what I do is go to someone's house and overdub bass on preexisting tracks. The interplay and interaction aren't there anymore. But it is what it is, and I still love what I do. I still have fun. And I still can't get over the fact that this is what I get to do for a living."